On September 16, 2025, a vaccination team supported by the SYDANI Initiative under its Saving Lives and Livelihoods (SLL) project met Amaka Okeke, a nursing mother, with her over six-weeks old son, Ifeanyi, in Akili-Ozizor, Ogbaru Local Government Area (LGA), Anambra State.

Shockingly, Ifeanyi had not received his Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, ideally administered at birth or within the first two weeks of life.

Amaka explained her dilemma. “Rain is consistent and flooding is fast coming. We are battling to save our crops. We go to farm every day. If we don’t harvest our crops now, even though premature, flood will destroy all. It is difficult for me to come to the PHC to immunize Ifeanyi.

Apart from the impending flooding, Amaka and her son live in one of the camps (shelters for farmers) far away. Fron there they visit the town only when it is almost sacrosanct to do so. For her, immunization is not one of such reasons as long as her son is not sick and in need of medical attention.

Her story mirrors that of many rural farmers who must choose between saving their livelihood and safeguarding their children’s health. More often, they choose the former over the latter.

The officer in charge (OIC) of the local primary health centre, Mrs Chioma Enweremadu, expressed concern: “The child was supposed to take BCG at birth or latest two weeks. Now, at six weeks, he is just receiving it. Many mothers have babies older than Ifeanyi who are yet to be vaccinated. They are busy on the farms, and unless we take the vaccines to them, these children will remain unprotected.”

Ifeanyi represents what global health experts describe as a zero-dose child – a child who has not received the first routine vaccine in the national immunization schedule.

When Enweremadu resumed as OIC of Akili Ozizor Primary Health Centre a year ago, she faced extremely poor turnout for immunization. “They don’t usually turn up,” she said regrettably. “They are farmers and would rather go to the farms or buy drugs from chemists nearby.

Before the on-going intervention, she sometimes immunizes only three or four children a week, with eight being the highest. With the rollout of the SLL project, health workers now take services directly to people’s homes and farms. “The impact has been dramatic,” Enweremadu said. “Last week, I immunized 32 children. This outreach strategy has transformed immunization delivery in the area,” she happily submitted.

Pregnant women also benefit as many of them who once ignored tetanus toxoid (TT) now receive doses at home. “Some first-time mothers have completed their second TT dose. It’s a breakthrough,” the OIC added. “SYDANI’s weekly incentives has kept health workers motivated and consistent.”

Zero-dose: Global and national burden

Zero-dose children highlight systemic gaps in health access – often linked to poverty, displacement, insecurity, or remote geography. Globally, more than 14 million children missed their first vaccines in 2024. Nigeria bears the world’s highest burden, with about 2.1 million zero-dose children, nearly 24% of its under-one population.

In Anambra, UNICEF reports that 39,805 children under two years have not received their first dose of the Pentavalent vaccine, which protects against five deadly diseases. Survey data from 2021 shows that 18.5% of children aged 12–23 months in Anambra are zero-dose, while 28.6% are under-immunized. Alarmingly, between 2016 and 2021, Anambra was the only South East state where Pentavalent 3 coverage declined.

These gaps are driven by inequities, poor infrastructure, socio-economic barriers, vaccine hesitancy, and the disruptions caused by COVID-19. In Anambra communities, insecurity and difficult terrains are exacerbating other factors.

State responses and missed gaps

However, the state government has been responding to the challenge by launching several initiatives such as the Big Catch Up (BCU) campaign aimed at restoring services and reaching children missed during COVID-19 years, followed by an integrated measles vaccination drive targeted over one million children across all wards.

Despite these efforts, children in rural and underserved communities remain at higher risk of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles, tetanus, and pertussis, underscoring the urgency of targeted interventions like SLL.

Hard-to-reach communities

The challenges are especially stark in Anambra West and Ogbaru LGAs – both riverine and flood-prone. Some parts of Ogbaru have also seen skirmishes of insecurity making access to vaccine more distant to residents.

“Many of the locals who had missed their immunization dates are now being discovered as we go to meet them,” said Mrs. Stella Ogolo, OIC of Umudora PHC in Anambra West LGA.

Mothers like Uchechukwu Nwankwo also confirm this. “We live in the camp far from the health centre. It is difficult and costly to go there to immunize my child,” she said.

Mrs. Edith Onwuka, the State Immunization Officer, SIO, highlighted the problem: “Anambra West and Ogbaru have many riverine settlements and farming camps that are hard to access, with Ogbaru further affected by insecurity. That is why we selected them for the SLL project.”

The SLL Project is a strategic intervention aimed at closing the persistent gaps in Nigeria’s immunization landscape. It addresses poor immunization coverage while laying a foundation for life-course vaccination. Funded by the Africa CDC in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation, it is implemented in Anambra by SYDANI Initiative for International Development through a sub-contract from AMREF.

SLL is improving routine immunization coverage through community engagement and demand creation by strengthening trust between communities and health providers through social mobilization, advocacy, and tailored communication. This is helping in dispelling myths and misconceptions about vaccines, thereby improving uptake.

It also targets hard-to-reach populations by focusing on remote, underserved, and conflict-affected areas, the project ensures equity in access. Mobile outreach services and door-to-door strategies extend coverage to children who would otherwise be missed.

To get the health workers on board, SLL organized refresher trainings for them on immunization practices, interpersonal communication, data recording, and outreach delivery. They were also trained on new tools and technologies (like digital dashboards and micro-planning systems) that make their work easier and more efficient.

According to Dr. Obiamaka Enwezor, SYDANI’s Project Manager, SLL is providing performance-based incentives to motivate health workers to reach more children, particularly zero-dose and under-immunized children. Under the project, job aids, registers, cold-chain support tools, and logistics assistance are provided to reduce the burden on frontline workers.

By improving vaccine availability and transport arrangements, health workers were spared the frustration of stockouts and broken cold chains. Health workers were actively engaged in micro-planning sessions and local problem-solving meetings, ensuring their insights shaped strategies. This gave them a sense of ownership rather than seeing the project as imposed.

Dr. Enwezor said, “We are ensuring that individuals whose lives are disrupted by natural disasters or insecurity still enjoy healthcare. We are also extending vaccines beyond children to women of childbearing age and even nine-year-old girls with HPV.”

More children, women reached

The outreach has fished out many under-immunized children like eight-month-old Ifeanyi Mbah from Umueze-Anam. He had received only BCG, Penta 1, and Penta 2, until a July 2025 when the outreach team discovered him and administered Penta 3, already weeks overdue.

The OIC, Lauretta Okonkwo shed light on the boy’s situation. “This is one of the greatest challenges we have here. The women will always say that they are busy with their farms especially now that they are striving to save their crops from impending flooding.”

The programme’s life-course approach also expands vaccination beyond children. “Now we can vaccinate mothers, children, and even older ones up to nine years. It is a wider scope of coverage,” explained Mrs. Bamidele, OIC of Ossamala PHC. With increased supplies, both pregnant and non-pregnant women now access tetanus-diphtheria vaccines more easily.

“This intervention is slightly different because it also focuses on adult vaccination. Before, we focused on children under five. Another good thing is that we now have adequate vaccines and can vaccinate the mother and her baby.

Progress amid fluctuations

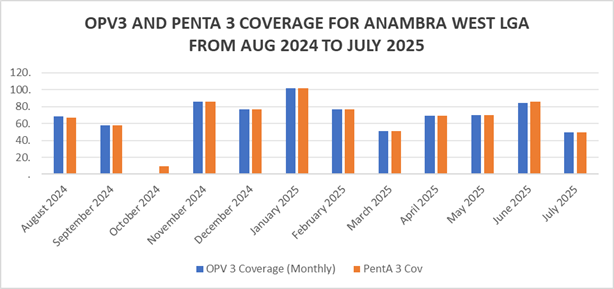

District Health Information Software, DHIS2 data from August 2024 to July 2025 shows fluctuating but improving coverage in the targeted LGAs in all the antigens. For instance, in August 2024, OPV3 coverage in Anambra West increased from 73.36% to 112.32% in July 2025. Within the same period, Penta 3 coverage rose from 73.36% to 112.32% in July 2025.

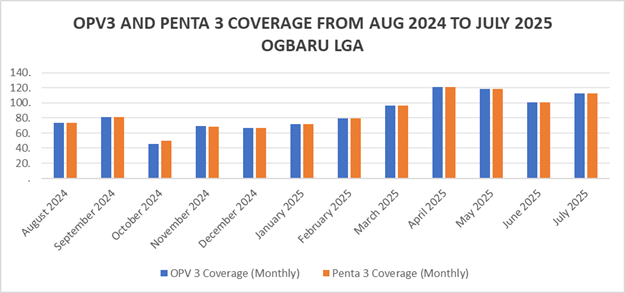

In Ogbaru LGA, OPV 3 which was at 68.43% in August 2024 rose to 84.66% in June and witnessed a sharp drop in July 2025 to 49.25%, while Penta 3 coverage standing at 66.87% in August 2024 rose in June to 86.1%. It however dropped to 49.25% in July 2025.

Dr. Placid Uliagbafusi, Director of Disease Control and Immunization the Anambra State Primary Health Care Development Agency, admitted the intervention is timely and transformative. “SYDANI is helping us improve immunization capacity and coverage,” he said.

“The success is largely improved health coverage in terms of routine and adult vaccination like HBV, TD. The uptake of those vaccines has increased. That is for us a plus. One of the indicators is the data you got from DHIS2, and the facility data,” says SYDANI State Lead, who wanted to be anonymous.

Successes are tied to rigorous monitoring and supervision among other factors. “SYDANI has its monitors and we also monitor from the state. From time to time, we visit the LGAs to see what they are doing,” said Mrs. Onwuka, the State Immunization Officer. “I personally joined outreaches in Ogbaru the last time I visited and observed increased willingness among families.”

Sustainability worries

Amidst the progress, health workers fear success may be reversed once donor support ends. “Seriously, I am afraid of possible erosion of these gains when SYDANI project ends. I don’t see the government funding the immunization at this rate. I just wish our government will take ownership and keep this momentum,” one of the OICs in Ogbaru LGA said.

However, Enweremadu’s worry is not just about government attitude. She also feared that beneficiaries may relapse after the SLL project because they are now used to sitting at home while vaccination team go to meet them.

SYDANI equally shares this fear around sustainability. The State Lead said the state government is expected to continue from where the organization stop but nothing is on ground to show commitment to sustainability. “The motivation is not there especially in terms of financing. The project will only be sustained when the money is there. But is there assurance that the money will come? The answer is no,” he said regrettably.

“Insecurity is still a challenge as our people don’t go out on Mondays due to the sit-at-home. I was in Ogbaru last Monday and apart from Okpoko which is like an urban area, the entire LGA was like a dead zone. Getting vehicle was almost impossible. I had to plead with somebody to convey me with her vehicle to the place I was going to. That is largely a setback for us because time is lost,” he laments.

“As River Niger is rising, the number of areas that we can reach is reducing. We wish that the intervention can also be scaled up to other LGAs but funding is limited.

He noted that though meeting up with targets was like a tall order for some of the vaccination teams, the challenge was addressed through consistent trainings.

Building on gains

The SLL project demonstrates that targeted outreach can significantly reduce zero-dose prevalence and strengthen routine immunization, even in difficult terrains – an approach that can turn things around if properly and sustainably implemented in any part of the country. Its life-course approach also ensures broader protection for mothers, children, and adolescents.

Yet sustainability remains the Achilles’ heel. Without state government ownership and long-term funding, the gains could easily reverse. The flood-prone, insecure communities of Anambra West and Ogbaru still need deliberate, locally-driven strategies to protect the most vulnerable.

According to the Coordinator, National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), in the state, Mr Obioha Agbakwuru, community ownership offers the surest assurance of sustainability.

“Most donor-driven projects in the past died after the interventions ended because they are makeshift and ephemeral. Communities must own their facilities. If the community does not take ownership, knowing that the facility belongs to them, sustainability will remain a challenge.”

“PHC is the first point of contact for every health issue at the local level. Community members must realize that the facility is their own and ensure that it works.”

On the part of the state government, Agbakwuru affirmed that much is expected in terms of funding for the PHCs. They have relied so much on assistance from NPHCDA, WHO SYDANI and other partner agencies providing additional resources occasionally. The states have this mentality that it is the responsibility of the Federal Government and partner agencies to provide resources for primary health care service delivery.

If the government pays attention to optimizing the operations of existing facilities, it will be better than building new ones while existing ones are suffering. State governments should provide adequate human resources for the facilities to thrive. They have roles to play but they’ve neglected them for far too long because of provisions from other sources.

The lessons are clear: doorstep delivery, flexible outreach, strong partnerships, and life-course vaccination can break barriers to immunization. But only sustained commitment will secure the promise of a healthier, fully immunized generation in Anambra and beyond.

This story is made possible with support from Nigeria Health Watch as part of the Solutions Journalism Africa Initiative