Alfred Ajayi

Climate change is no longer a distant problem but a nearby existential threat. Across Nigeria and Africa, it is disrupting rainfall, increasing heatwaves, worsening floods, and threatening food security. But here’s the key: not everyone contributes equally to the problem, and not everyone is affected in the same way. Unfortunately, those who contribute the least suffer the most, hence the growing clamour for climate justice.

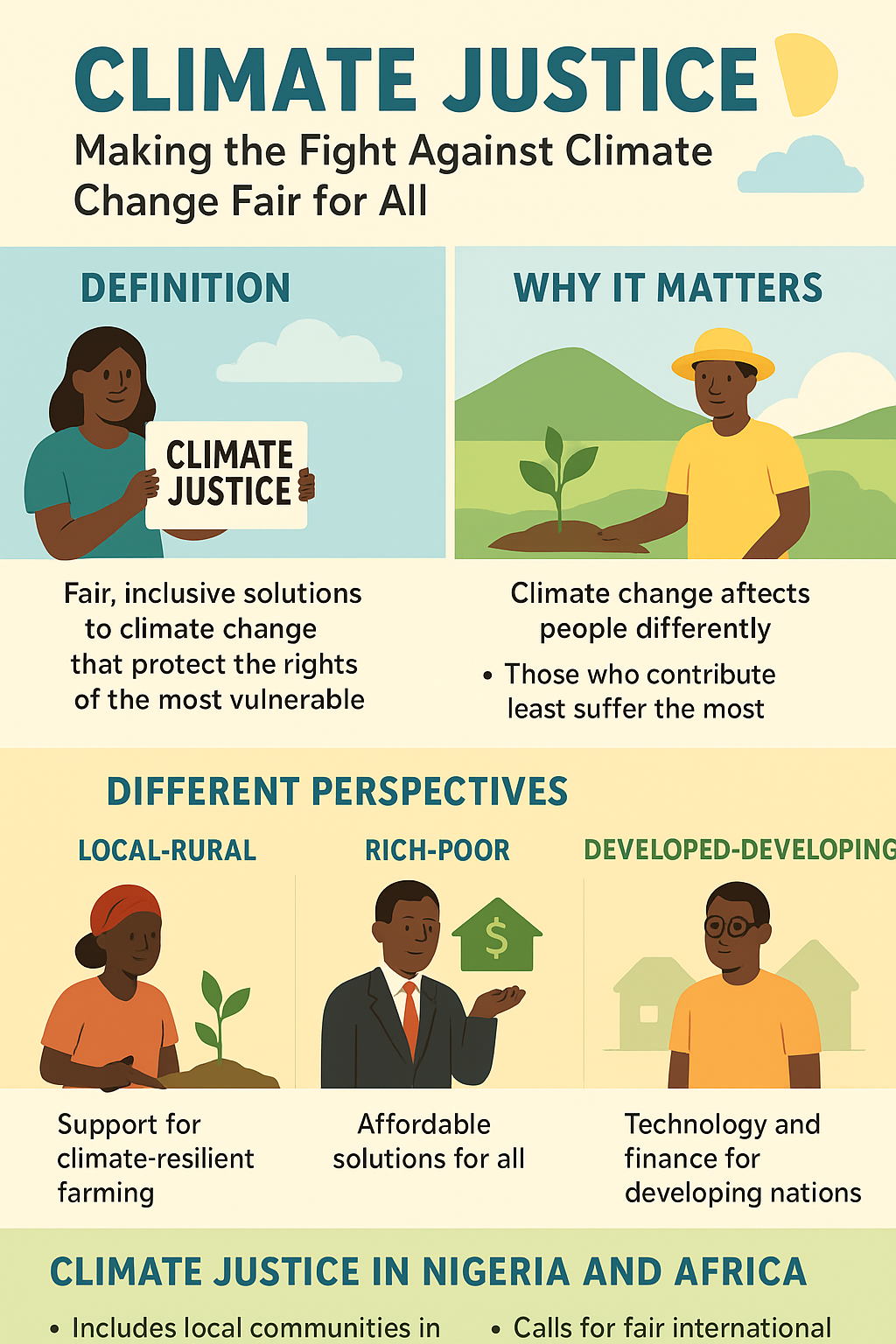

Climate justice is the moral and ethical principle seeking to address the disproportionate impact of climate change on vulnerable communities and future generations. It advocates for equitable solutions that prioritize the needs of those who are most affected by climate change, strive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and ensure that the burdens and benefits of climate action are distributed fairly, taking into account historical and systemic inequalities. Ultimately, climate justice pushes for a more inclusive and sustainable approach to addressing the global climate crisis.

The Climate Justice Global Alliance (CJGA) employes a youth-driven combination of education and activism to reduce global climate injustice, an aspect of SDG 13 under the UN Agenda 2030, targeting making changes in areas most impacted by climate change and environmental degradation through political activism and the distribution of original publications on climate justice and Earth sciences.

Climate justice requires ensuring that solutions to climate change are fair, inclusive, and protective of the rights of the most vulnerable, while holding those most responsible for causing climate change accountable. Climate justice asks pertinent questions – Who is causing the most damage? Who is suffering the most? Who has the resources to act? Most importantly, how can we ensure no one is left behind?

Why climate justice matters

Climate justice is not only an international imperative but a cross-cutting responsibility owed to the world’s most vulnerable citizens, communities and nations. This matters because climate change doesn’t treat everyone equally.

For instance, a drought in northern Nigeria can destroy a smallholder farmer’s entire livelihood, while a wealthy business owner in Lagos might simply pay more for imported food. A flood in Bayelsa may sweep away the only health clinic in a fishing village, while an oil company’s headquarters in Abuja remains safe.

Climate justice justifiably puts people at the centre of climate action, ensures the burden of change is shared fairly and connects local realities to global responsibilities. In rural communities across Nigeria and Africa, most people live close to the land – farming, fishing, or herding are being hit the hardest by climate change. Drought in the Sahel is reducing grazing land, floods in Anambra, Kogi etc are washing away farmlands and homes.

Erratic rains are making seeds to rot in the soil or while crops are failing. Yet, these communities have done very little to cause climate change as they most dwellers neither own cars, factories nor even use electricity regularly.

Justice for farming communities

In their case, climate justice means giving rural communities a voice in climate policies, providing resources and training for climate-resilient farming, ensuring early warning systems for floods and droughts reach them in their local languages.

The Great Green Wall project in northern Nigeria aims to restore degraded land, provide jobs, and slow desertification. The project was designed to help the communities most affected to adapt to changing conditions while preserving their dignity. Sadly, recent reports are pointing to the failure of the project.

Also, wealth influences impacts of climate change on people. For instance, the rich individuals can afford generators during power cuts, bottled water during droughts, and air conditioning during heatwaves, while the poor ones are forced to drink unsafe water, endure extreme heat, or lose their small shops to flooding.

Climate justice demands that the costs of climate action like switching to cleaner energy should not put unfair burden on low-income households. There should be subsidies for solar panels in rural areas, affordable public transport instead of fuel price hikes without generally beneficial alternatives, compensation for market women whose goods are destroyed in flood-prone areas.

Country-level justice

At the country-level, the Brookings affirms that the global climate crisis is deeply unequal. Developed countries (like the US, UK, Germany) have emitted the bulk of greenhouse gases since the Industrial Revolution. Developing countries (like Nigeria, Kenya, Bangladesh) have contributed far less but face some of the worst impacts. Climate justice therefore calls on rich nations cut emissions faster, provide finance, technology, and capacity-building to developing countries, while compensating loss and damage — such as the destruction of homes, livelihoods, and cultural heritage from climate disasters.

At COP27 in Egypt (2022), countries agreed to set up a Loss and Damage Fund to support vulnerable nations. This is a climate justice milestone — though Nigeria and Africa still push for fair and fast implementation.

There is also climate justice from the gender perspective. Women, especially in rural Africa, are more exposed to climate risks because they often farm small plots of land, fetch water from long distances, and care for children and the elderly during disasters among other gender-assigned roles. However, they are not adequately involved in climate decision making processes.

Here, climate justice means including women in decision-making about climate action as powerful agents of change, supporting female-led climate enterprises, ensuring that relief and recovery programmess meet their specific needs. For instance, women’s cooperatives in Uganda have successfully adopted clean cooking stoves, reducing deforestation and indoor air pollution. Similar projects in Nigeria could address health, climate, and gender equity at the same time.

From the youth perspective, Nigeria has one of the largest youth populations in the world who will live with the effects of today’s climate choices for decades. For them, climate justice means intensive climate education in schools, support for green jobs and innovation, as well as inclusion in policy-making spaces as decision-makers.

Climate justice versus mitigation and adaptation

Climate justice strengthens both mitigation (reducing emissions) and adaptation (adjusting to impacts). In terms of mitigation, when climate policies are fair to all, people are more likely to support them, communities feel ownership of solutions and there is less resistance from those who might otherwise bear the costs. Replacing diesel generators with community solar mini-grids in rural Nigeria will cut emissions and provides affordable, reliable power.

Talking adaptation, climate justice means take adaptation resources to where they are most needed. These include: flood barriers in riverine communities, drought-resistant seeds for farmers in dry regions, health facilities prepared for heat-related illnesses among other adaptation measures.

In Mozambique, cyclone-prone villages have community-based disaster preparedness teams, supported by both local and international funding. This is a justice-focused adaptation approach which Nigeria can learn from.

Nigeria and Africa stand at the intersection of vulnerability and opportunity. Vulnerability because our economies and livelihoods are closely tied to natural resources sensitive to climate shifts and opportunity because we can leapfrog to greener technologies without repeating the polluting paths of developed countries.

Climate justice in Nigeria/Africa compels policy alignment – implementing climate laws with strong social safeguards. It also demands greater finance. African countries must collectively push for developed nations to meet their $100 billion per year climate finance pledge. Also, our governments must ensure that climate adaptation plans are community-driven. They must implement climate related policies and laws more stringently holding both local and international polluters responsible.

Climate justice is about more than protecting the planet — it is about protecting people, especially those who did the least to cause the crisis but are suffering the most.

First published by Radio Nigeria